Have you or your company run into a utility patent that makes you ask: “do we have an infringement problem?”

Perhaps you received a threatening “cease and desist” letter from a competitor who claims to own a patent that prevents you from selling your product—or demands a patent licensing fee to continue your sales.[1] Maybe you did some “Googling” and found a patent that looks to be solving a similar problem as your product, or even has figures that resemble your product. Or perhaps you hired a patent agent or attorney to file a patent application covering your product with the United States and Trademark Office (USTPO), and the patent examiner rejected your application in response to another similar-looking patent that came before.

Whatever the case, it’s important to understand that the ultimate question of whether you infringe requires a special legal analysis. Below we provide a summary of some key considerations that generally go into a proper infringement analysis—as well as pitfalls to avoid. But before getting to these considerations, it’s helpful to understanding the various pieces and parts of a patent.

1) Background: Patent Pieces and Parts

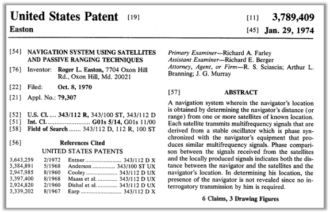

The claims are the name of the game in a patent infringement analysis. The claims are generally located at the end of the patent, which comes after the patent’s front page, drawings, and written description. Take as an example U.S. Patent No. 3,789,409 that issued in 1974 to Roger L. Easton, who has been dubbed the “Father of GPS.”[2] The front page of Easton’s ‘409 Patent is excerpted below.

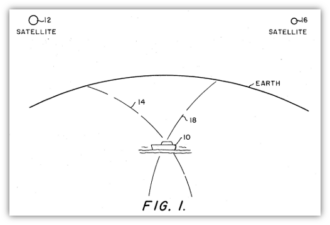

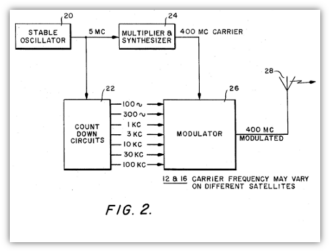

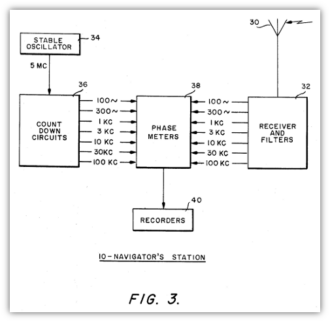

What follows is a set of drawings—Figures 1–3 in the ’409 Patent example excerpted below.

After the drawings comes a specification containing a written description of the invention. The written description is required to set forth “the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make and use the same.”[3] The specification of Easton’s ‘409 Patent starts on its fourth page excepted below.

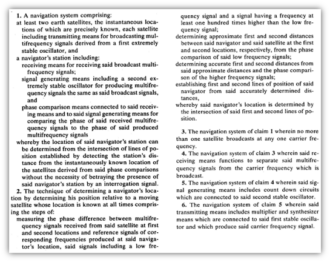

The specification then generally ends with one or more numbered “claims.” The purpose of the claims is to particularly point out and distinctly claim the subject matter that the inventor(s) regards as the invention.[4] What Mr. Easton regarded as his invention in the ‘409 Patent is set forth in his numbered claims 1–6 excerpted below.

2) A Proper Infringement Analysis: Two Steps

With the various patent pieces and parts in mind, there are two steps to a patent infringement analysis.[5] The first step is determining the meaning and scope of the claims—i.e., the meaning and scope of what’s recited in the consecutively numbered claim(s) at the end of the specification.[6] This process is known as “claim construction.”[7] The second step is comparing the properly construed claims to the product or method accused of infringement.[8]

3) Infringement Analysis Step No. 1: Claim Construction

It’s well established that a patent’s claims define the invention to which the patent holder is entitled the right to prevent others from practicing.[9] In claim construction, the words of the claims are generally given their ordinary and customary meaning as they would be understood by “a person of ordinary skill in the art”—a POSITA for short—at the time of the invention.[10]

A) Do Read the Claims in Context of the Entire Patent

How does one determine how a POSITA would have understood the words the claims? By reading them in context of the entire patent.[11] This includes the written record of what transpired over the course of the patent applicant’s bid with the Patent Office to gain allowance of the patent—known as the “prosecution history.”[12] Together, the patent and prosecution history are known as “intrinsic evidence” of claim construction.

For example, courts recognized that the prosecution history can inform the meaning of the claim language by demonstrating how the inventor understood the invention and whether the inventor limited the invention during prosecution, making the claim scope narrower than it would otherwise be.

As another example, the claim scope may be narrower (or broader) than it otherwise would be if the inventor has given a special definition to a term used in the claims that differs from the meaning that the term might otherwise have. When this happens, the inventor’s “lexicography” controls regardless of what a dictionary or expert in the field might say.[13]

As a further example, a claim may recite a function without reciting a term having sufficient structure for performing that function.[14] This is known as a “means-plus-function” claim.[15] When this happens, the claim must be construed to include the structure (if any) disclosed in the specification as corresponding to the recited function (or equivalent structures). A common indication that a claim is “means-plus-function” is where the claim literally recites only a “means” for performing a function. But other “nonce” words may also turn the claim into “means-plus-function,” such as a “module,” “element,” or “device” for performing a function.[16] For example, if a claim recites a “module for determining a GPS coordinate,” and the specification discloses a computer executing a specific 10-step algorithm to determine a GPS coordinate, then claim construction may require that the claim be limited to a computer executing the specification’s 10-step algorithm (or equivalents) for determining the GPS coordinate.

B) Do Not Rule Out Evidence Beyond the Patent and Prosecution History

Evidence outside of the patent and prosecution history—known as “extrinsic evidence”—can also shed light on the meaning and scope of the claims for claim construction.[17] Common types of extrinsic evidence include testimony from POSITAs and the inventors themselves, technical dictionaries, and authoritative treatises in the field.[18] However, courts generally find the intrinsic evidence to be most significant.[19]

C) Do Not Focus on the Title, Abstract, Drawings, and Written Description in Isolation

While it’s important to consider the patent as a whole in construing the claims, it’s critical to avoid over relying on what may seem like straightforward guideposts—such as titles, abstracts, drawings, and written descriptions. This is not to say that claim construction should ignore the rest of the patent. (As discussed, the proper analysis considers the claims in view of the patent as whole.) But interpreting the claims to be limited to specific features or embodiments described in portions of the patent outside of the claims is generally prohibited.

Titles. Take again as an example Easton’s ’409 Patent. Easton’s ‘409 Patent is titled “Navigation System Using Satellites and Passive Ranging Techniques” (excepted below).

But the tile does not mean that anyone who uses satellites and passive ranging techniques to implement a navigation system infringes the patent’s claims.[20] Conversely, the title does not mean that anyone who implements a satellite-based navigation system using active ranging (instead of passive ranging) avoids infringement. For instance, it’s possible that that the actual patent claims could be ranging technology agnostic.[21]

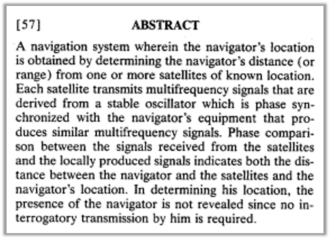

Abstracts. Easton’s ’409 Patent also has an Abstract (excepted below)

Although courts may look to a patent’s abstract in determining the scope of a claimed invention as part of claim construction,[22] you’d be remiss to interpret the claims using only the abstract, which is not intended to set forth specific bounds of the claimed invention. The purpose of the abstract is instead “to enable the United States Patent Office and the public generally to determine quickly from a cursory inspection the nature and gist the technical disclosure.”[23]

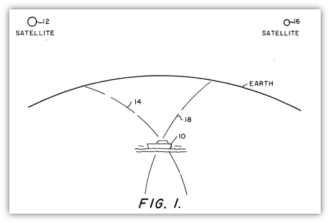

Drawings. A patent’s drawings are likewise generally un-controlling.[24] For example, Easton’s ’409 Patent includes a Figure 1 (excerpted below) that it describes as drawing of “a perspective view of the invention.”[25] The drawing shows two satellites 12 and 16, a ship 10, and EARTH with a first line of position 14 intersecting a second line of position 18.[26] This, however, does not mean that any system with two satellites and a ship that sits on intersecting lines of position on Earth infringes. And conversely, Figure 1 does not mean that adding a third satellite—or positioning the two satellites at different locations relative to Earth—avoids infringement. This is because patent drawings do not operate to limit the patent claims to the specific configurations depicted in the drawings.[27]

Written Descriptions. Even the written description itself—responsible for clearly describing the manner and process of making and using the invention—does not necessarily limit a patent’s claims.[28] This is true even where the written description sets forth only a single embodiment (or version) of an invention.[29]

4) Infringement Analysis Step No. 2: Comparing the Construed Claims to The Accused Product or Method

The key to completing the infringement analysis is comparing each patent claim, as construed, to the accused product or method.

A) Do Consider Whether the Accused Product or Method Contains Each Element of the Construed Claims (or Substantial Equivalents)

The proper infringement analysis asks whether the accused product or method contains every claimed element of the patented invention—or the equivalent of every claimed element.[30] This is known as the “all-elements rule.”[31] But remember that only one claim needs to be infringed for liability to attach. So even if a patent contains 20 claims, infringement exists if the “all-elements rule” is met for only a single claim.

B) Do Not Disregard the “Doctrine of Equivalents”

Literal infringement occurs when every claim set forth in a claim as construed is found in the accused product or method exactly. [32] But infringement can also occur under the “doctrine of equivalents.” [33] Subject to certain limitations that are beyond the scope of this post, the doctrine may apply when the accused product or method performs substantially the same function in substantially the same way with substantially the same result as each element in the construed claim.[34]

C) Do Not Neglect to Consider Whether You Might Indirectly Infringe

Direct infringement occurs when you make, use, offer to sell, or sell any patented invention within the United States or import the patented invention into the United States.[35]

But even if you yourself do not take these actions, you may face liability for indirect infringement if you actively induce others to directly infringe a patent claim.[36] You may also face liability if you sell or offer to sell within the United States—or import into the United States—a component of a patent claim if (1) the component constitutes a material part of the claimed invention, (2) you know that the component is especially made or adapted for use in an infringement of the patent, and (3) the component is not a staple article or commodity of commerce suitable for substantial noninfringing use.

5) Conclusion

As this blog post intends to emphasize, a meaningful utility patent infringement analysis involves far more than simply asking: “is my product the same as what’s shown in this patent?” Properly assessing utility patent infringement risks merits a careful and informed study. While we hope that this post provides helpful backdrop, it is crucial that those facing potential infringement issues consult an attorney who specializes in patent infringement issues, as this area of the law is very nuanced.

If the infringement analysis is not correctly performed, one may find themself embroiled in unanticipated legal challenges that have more merit than expected. Or they might end up unnecessarily redesigning their product—or even ceasing production—to avoid perceived infringement, when a proper analysis might have revealed that there was no real infringement risk to begin with.

[1] Those faced with the threat of patent litigation will do well to consider Harness IP’s recent post titled, Is Intellectual Property Litigation in Your Future? Do This Now! (Sep. 26, 2024), available at https://www.harnessip.com/blog/2024/09/26/intellectual-property-litigation/. Those accused of patent infringement may likewise benefit from reviewing Harness IP’s recent post titled, The 7 Things You Don’t Say (In Writing) When Your Company is Accused of Patent Infringement (Nov. 19, 2024), available at https://www.harnessip.com/blog/2024/11/19/when-accused-of-patent-infringement/. [Jocelyn – See comment above for this footnote]

[2] See Parry, Father of GPS and Pioneer of Satellite Telemtry and Timing Inducted into National Inventors Hall of Fame, U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (Mar. 30, 2012), https://www.nrl.navy.mil/Media/News/Article/2578456/father-of-gps-and-pioneer-of-satellite-telemetry-and-timing-inducted-into-natio/.

[3] 35 U.S.C. § 112(a).

[4] 35 U.S.C. § 112(b).

[5] Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc., 52 F.3d 967, 976 (Fed. Cir. 1995).

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1312 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (“It is a ‘bedrock principle’ of patent law that the claims of a patent define the invention to which the patentee is entitled the right to exclude,” cleaned up).

[10] Id. at 1326.

[11] Id.

[12] Id. at 1317 (“The prosecution history . . . consists of the complete record of the proceedings before the PTO and includes the prior art cited during the examination of the patent. Like the specification, the prosecution history provides evidence of how the [Patent Office] and the inventor understood the patent.”) see also Markman, 52 F.3d at 985 (“[I]t is not unusual for there to be a significant difference between what an inventor thinks his patented invention is and what the ultimate scope of the claims is after allowance by the [Patent Office].”).

[13] See Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1316.

[14] See Dyfan, LLC v. Target Corp., 28 F.4th 1360, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2022).

[15] See Williamson v. Citrix Online, LLC, 792 F.3d 1339, 1347 (Fed. Cir. 2015).

[16] See, e.g., id. at 1349.

[17] See Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1317.

[18] See id. at 1318.

[19] See id.

[20] See, e.g., Pitney Bowes, Inc. v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 182 F.3d 1298, 1312 (Fed. Cir. 1999) (“[W]e certainly will not read limitations into the claims from the patent title.”)

[21] See Intamin, Ltd. v. Magnetar Techs., Corp., 483 F.3d 1328, 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (“A patentee may draft different claims to cover different embodiments.”).

[22] Hill-Rom Co. v. Kinetic Concepts, Inc., 209 F.3d 1337, 1341 n.* (Fed. Cir. 2000) (“[W]e have frequently looked to the abstract to determine the scope of the invention.”)

[23] See 37 C.F.R. 172(b) (emphasis added).

[24] See, e.g., Anchor Wall Sys. v. Rockwood Retaining Walls, 340 F.3d 1298, 1306-07 (Fed. Cir. 2003)

[25] U.S. Patent No. 3,789,409 at 2:11.

[26] Id. at 2:30-44.

[27] See Anchor Wall Sys., 340 F.3d at 1307; see also MBO Labs., Inc. v. Becton, Dickinson & Co., 474 F.3d 1323, 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (“[P]atent coverage is not necessarily limited to inventions that look like the ones in the figures.”)

[28] Markman, 52 F.3d at 980 (“The written description part of the specification itself does not delimit the right to exclude. That is the function and purpose of claims.”)

[29] Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1323 (“[W]e have expressly rejected the contention that if a patent describes only a single embodiment, the claims of the patent must be construed as being limited to that embodiment.”)

[30] See Kustom Signals, Inc. v. Applied Concepts, Inc., 264 F.3d 1326, 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2001).

[31] Id.

[32] Advanced Steel Recovery, LLC v. X-Body Equip., Inc., 808 F.3d 1313, 1319 (Fed. Cir. 2015).

[33] Id.

[34] See AquaTex Indus. v. Techniche Sols., 479 F.3d 1320, 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2007)

[35] This assumes that the patent has not expired and you lack permission from the patent owner. See 35 U.S.C. § 271(a).

[36] 35 U.S.C. 271(b).